Kaseya has a customer base of roughly 35,000 businesses and organizations. These consist of approximately 17,000 managed service providers, 18,000 direct/VAR customers and a significant number of end users at the organizations they support. There is certainly a large attack surface offered to threat actors who might compromise the Kaseya VSA software.

In the recent ransomware incident that occurred in July 2021, the industry learned that 50-60 MSPs and their managed customers were encrypted by the REvil ransomware gang through the Kaseya VSA remote monitoring and management software.

With just 50-60 MSPs affected out of a potential 17,000 or 35,000, that leaves us with a large lingering question… “Why weren’t there more victims?”

That is to say, in a more pointed manner, “Shouldn’t there have been more carnage?”

Immediately after recognizing the attack, Kaseya took action to shut down their VSA SaaS platform and instructed customers to shut down all on-prem servers around 1400 ET. This shutdown could be used as an explanation for why such a small number of VSA customers were affected by such a serious and widespread vulnerability. However, there are two important things to consider here.

First, according to Kaseya, the SaaS platform was not vulnerable to the exploited vulnerabilities. The shutdown of the SaaS platform was a reactionary measure taken out of an abundance of caution but should not have directly impacted the number of exploited victims.

Second, the threat actors synchronized this attack to occur at 1230 ET on July 2. This means that initial exploitation of VSA servers took place prior to the shutdown. We observed suspicious Kaseya procedure execution as early as 0109 ET on July 2. By the time VSA customers shut down their servers, any exploitation would have already been complete, and attacks would have happened as planned. Anecdotally, we have received reports of some customers finding remnants of the malicious stored procedures when bringing VSA servers back online; however, any order to shut down after 1230 ET would not have minimized the number of compromised MSPs.

Huntress, in addition to other industry players, has observed that the ransomware incident used an attack chain consisting of (1) an authentication bypass, (2) arbitrary file upload and (3) remote code execution.

What we and others still wonder is how did the hackers get the necessary information to bypass authentication?

Following the exploitation steps, the first malicious request was to the public-facing file /dl.asp.

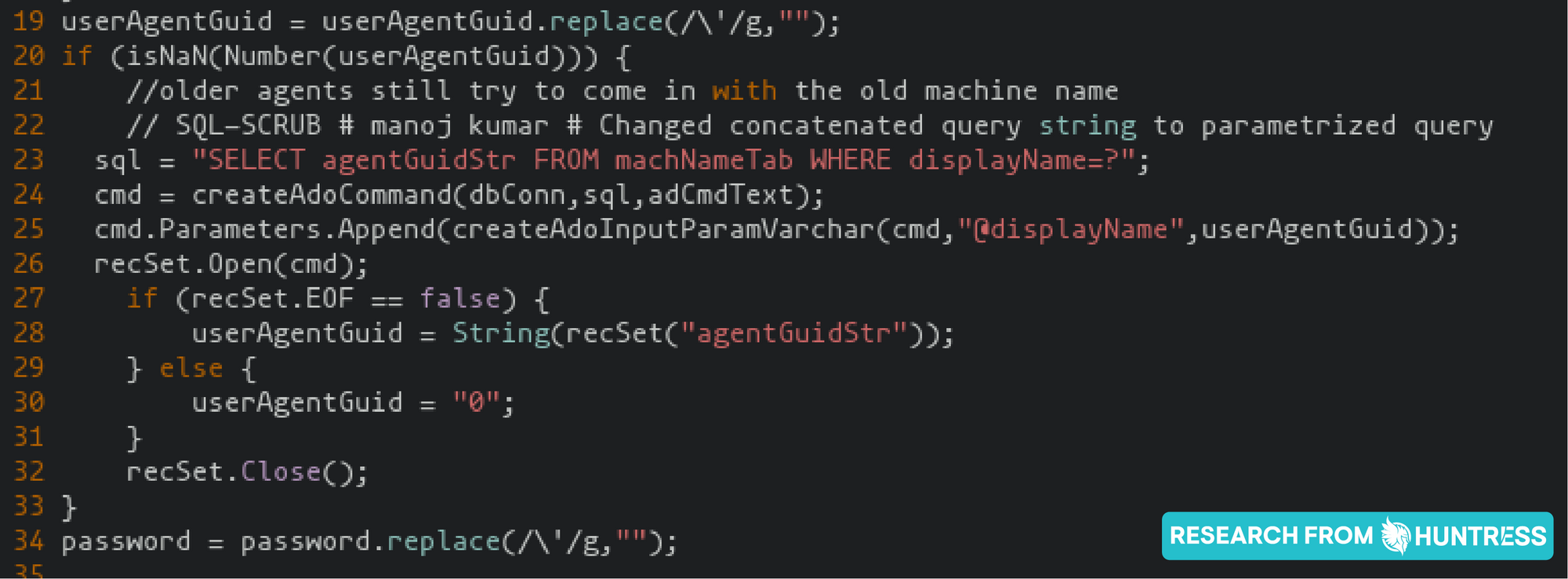

This file contained a logic flaw in the authentication process. If a password was not supplied, but a valid unique Kaseya agent identifier (an Agent GUID) was, the end user would be logged in successfully. At that point, the actor could access other functionality that required authentication—all without a traditional password.

In the analysis of the attack, we have seen and confirmed malicious access by just providing a unique agent GUID. We had not seen any indicators that the threat actors brute-forced agent GUIDs; they simply knew these prior. There were no failed attempts present in any logs.

But still, there are lingering questions: How did the threat actors have a unique Agent GUID?

We believe there are a few potential options.

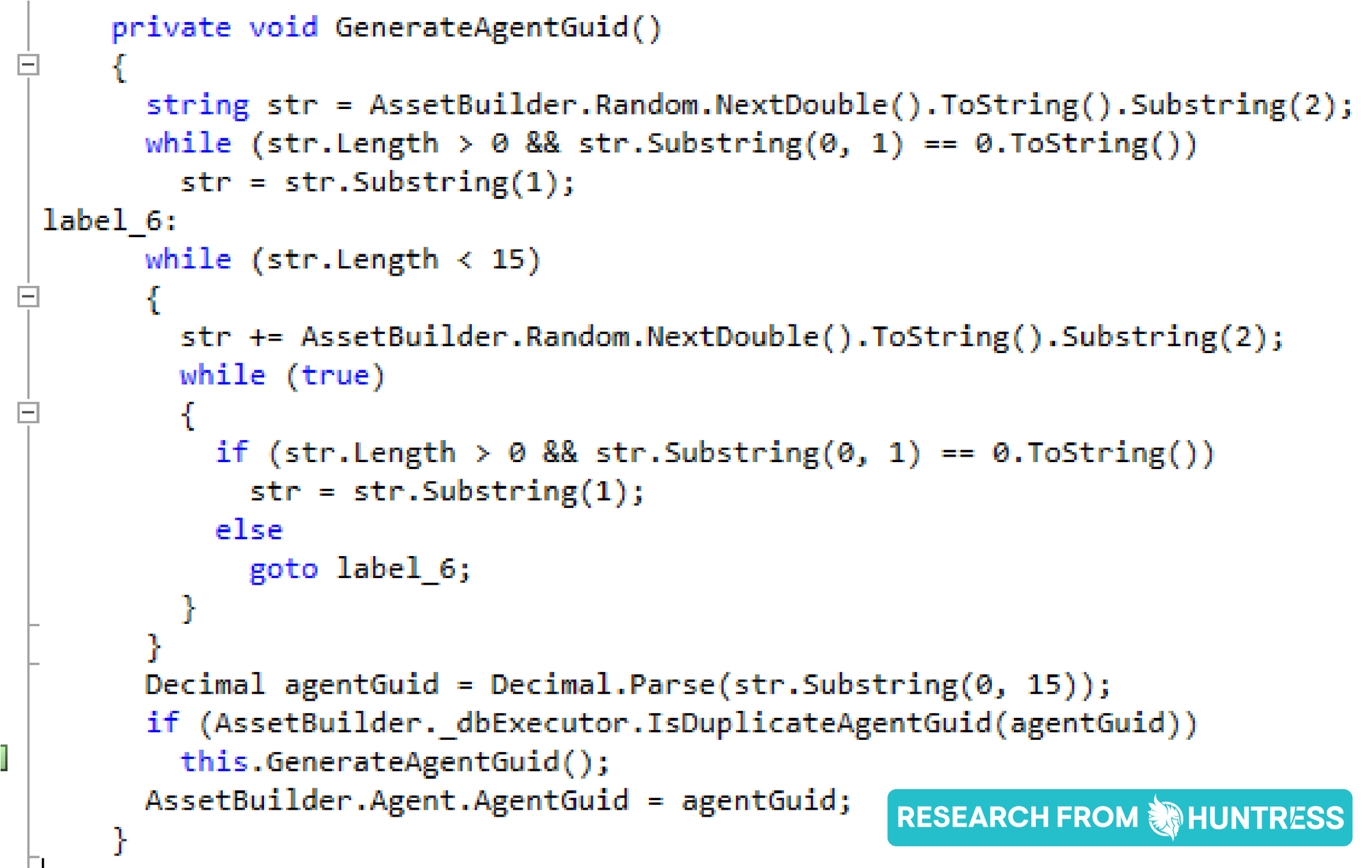

/dl.asp can accept either an Agent GUID or a Display Name. However, the Display Name (e.g. vsahost.root.kserver) is not the actual hostname, varies from organization to organization (with no standard across Kaseya VSA usage) and does not appear to be predictable. As for the Agent GUID, it is a randomly generated 15-character string that is also not based on the hostname in any way. Based on the logs we observed from the incident, we did not see any indication of attempted brute-forcing of the Agent GUID or Display Name.

Excerpt from /dl.asp showing acceptance of either Agent GUID or Display Name

Based on these details, we have low confidence that the attackers were able to repeatedly predict a valid Agent GUID or Display Name on their first attempt.

The intended purpose of the original /dl.asp file is to create and download a new agent installer. The default agent installer is available for download without authentication. After successful installation, the user will have access to a new and valid Agent GUID for the newly registered device.

In the logs we have, we identified a suspicious agent that registered at ~0100 ET, which could have been the malicious agent. However, we didn’t have the content of the requests or a packet capture to verify how that agent was used. This mysterious agent was also deleted from the database we received, which is also suspicious. It seems unlikely that an MSP would register an agent at 0100 ET on the Friday of a holiday weekend.

Although the Huntress ThreatOps team could not find definitive proof that a “rogue” agent was registered, we feel this option is a plausible scenario. However, it’s worth asking “Why didn’t the threat actor compromise more VSA customers?” if this method was (ab)used.

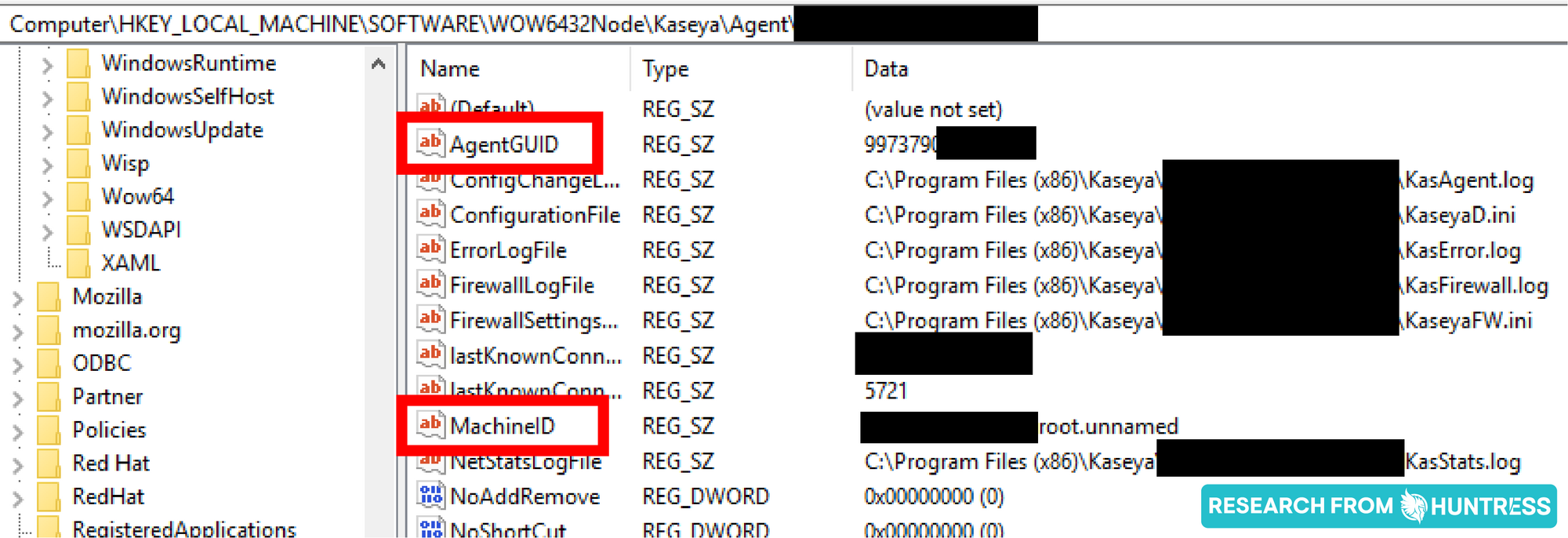

If the threat actor already had access to a host managed by VSA, they could have retrieved its Agent GUID from the registry and then used that for the authentication bypass.

Although we haven’t discovered evidence to support this theory, this option is certainly possible and could explain the relatively small blast radius we observed during the attack. Requiring initial access to a compromised host running a VSA agent is an interesting dependency which would make this a much more sophisticated and organized attack.

While there are seven vulnerabilities that were disclosed by DIVD and Kaseya has publicly patched, there is still a potential for more.

With that said, even the publicly identified vulnerabilities could include capabilities that might offer a valid Agent GUID.

Notably, these are the interesting vulnerabilities that might leak information:

While strict SQL injection was not observed in the logs, just as with the other possibilities, it could have been done long before the actual exploitation and potentially from different IP addresses.

It is no secret that in recent years, Kaseya VSA has fallen victim to security incidents. There have been dumps shared on Tor Hidden Services and the corners and crevices of the “dark web,” and while we have not been able to confirm this, there is the potential that Agent GUIDs were already out and about.

If this were the case, there would need to be a mapping between the Agent GUID and the respective organization. If that information were included in a leak, that could provide all the information necessary for the authentication bypass. If that mapping was not present and the threat actor had access to just solely Agent GUIDs, correlating them to the specific organization would be much harder to do.

We acknowledge this is purely discussion and speculation. Considering the gravity of this widespread ransomware attack, we have to ask “Why was this constrained to only 50-60 affected MSPs, and why not more?”

We hope that outlining these potential ideas on the origins of this attack showcase the level of exploration and understanding vendors and customers should be seeking—but also raise the notion that this could have been much worse.

Were there other vulnerabilities we were unaware of? Was there missing intelligence in Screenshot.jpg that might tell more of the big picture? Were multiple agent GUIDs previously leaked or already public information? Did threat actors learn from previous incidents (like Colonial Pipeline) that a much larger impact might invite government intervention? We just don’t know.

If any organizations have a full copy of this malicious Screenshot.jpg, please share your findings and the file with us at support[at]huntress.com.

What we do know, however, is that the blast radius for this incident was significantly smaller than what it could have been. When headlines and news articles fly claiming this is the “biggest ransomware attack so far,” the industry has to hone in on that key component: "so far.”

We can be thankful that this attack was relatively limited, but we can’t lose sight and not dig deeper to understand why so we can be better prepared for whatever the next threat is. What’s lurking around the corner might just be worse…

* Special thanks to fellow Huntress Security Researchers Caleb Stewart and Dave Kleinatland for their input and help in preparing this article.

Get insider access to Huntress tradecraft, killer events, and the freshest blog updates.